By Ruby Angela Saleh Sister of Fahim Saleh

On July 14th at 10:47 pm, my phone rang. I was in bed next to my husband and had just begun dozing off, but I answered because it was my aunt, calling from New York. “I have some very bad news,” she said.

She sounded spooked and was reluctant to divulge more, so I knew something really bad had happened to someone in my immediate family. My shoulders stiffened while the rest of my body went limp. Maybe one of my parents had Covid?

“What happened?“ I kept asking. “What happened?” I was having trouble drawing a breath. I put the phone on speaker so my husband could listen.

“It’s very bad,” she said.

“Just tell me, Aunty. What happened?”

“Fahim isn’t with us anymore,” she said.

Her words didn’t make sense. “What do you mean?” How could my healthy, vibrant, creative, beautiful 33-year-old baby brother not be “with us anymore”?

Then she said, “Somebody murdered him.”

“What are you talking about?” I screamed.

I hung up and called my sister, who cried out my name. She said she was with the detective and couldn’t talk long. “We hadn’t heard from him for a while, so A went to his apartment to check on him,” she said.

A is my 30-year-old cousin. Fahim, who had become a successful tech entrepreneur before he was old enough to drive, had inspired her to become a coder. “She found his torso in his living room,” my sister said. “I have to go. I’m with the detective.”

I dropped the phone and crawled onto the wooden floor, touching its cold, hard surface with the palms of my hands. I shook my head. “No, no,” I said, my hair falling over my face. “What are they saying?”

I looked up at my husband. He was already crying, as if he had accepted these words about my brother as truth. His crying didn’t make sense to me because this news couldn’t possibly be real.

I flew across the Atlantic to New York the next day. Internet headlines about my brother’s murder proliferated.

“CEO Found Dismembered In Manhattan Apartment,” one read. “NYC Cops Find Headless, Limbless Man Next To Electric Saw” another explained. This was MY baby brother they were talking about.

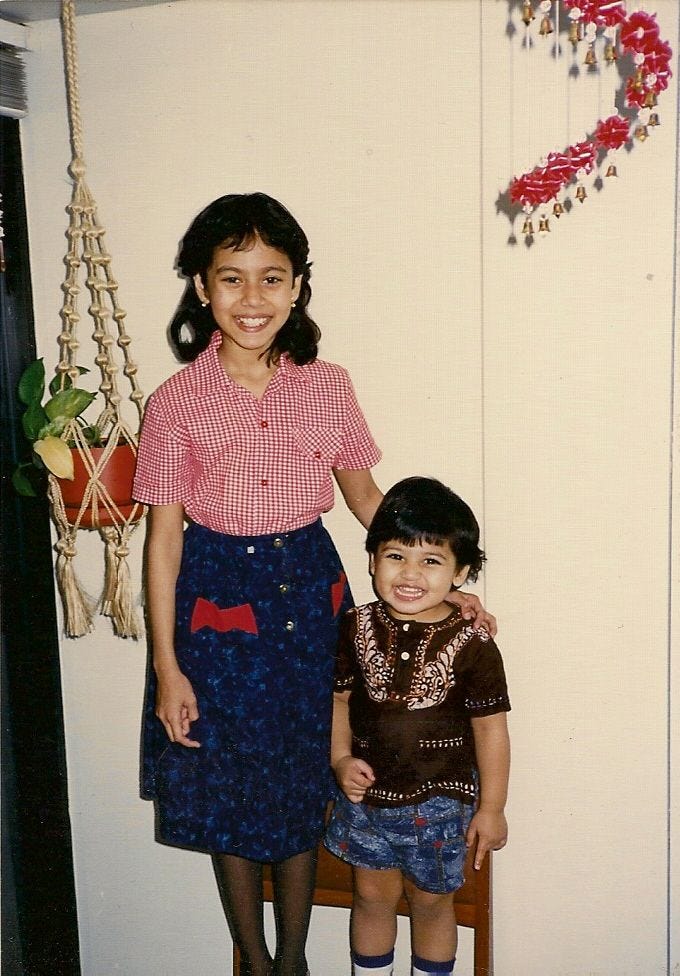

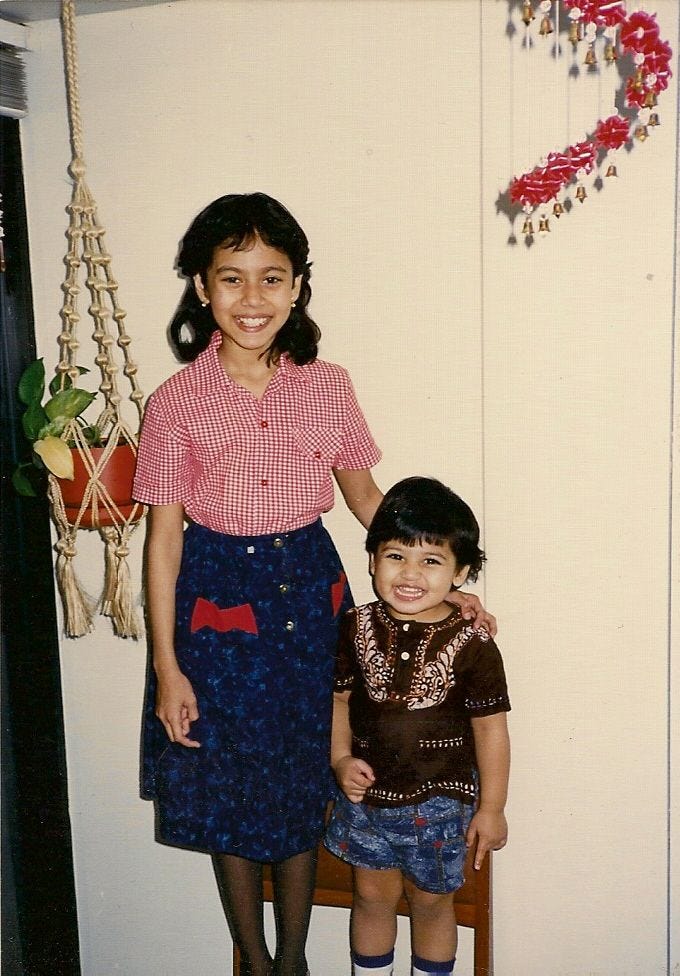

MY Fahim, whom, when I was eight years old, my parents brought home from the hospital to me in an orange fleece blanket.

While we were growing up, I felt more like a mother to Fahim than a sister. When he was a toddler too wild to finish a meal, I ran after him with spoonfuls of rice and chicken.

I gave him baths, I changed his diapers, and I was petrified the first time I saw his nose bleed. Something horrible is happening to him, I thought, watching blood gush onto his little yellow shirt. He was three then. I was eleven.

Thirty years later, I was learning that Fahim’s head and limbs had been discarded in a trash bag. Someone had cut my brother’s body into pieces and tossed the pieces into a garbage bag, as if his life, his body, his existence had had no meaning or value.

Messages began pouring in from friends. “I don’t know what to say,” most of them began.

“Oh, L, who would do this to my baby, my poor baby, my poor sweet brother?” I replied to one of my best friends. “This still feels like a nightmare I will wake up from…my poor sweet baby.”

We tried to protect our parents as much as we could in those first few days, but my sister and I spoke openly with each other.

We had the same thoughts: Had he been scared? Had he begged for his life? Had he suffered? And if so, how much?

We thought we wanted to know everything, but what we really wanted was to conclude that he hadn’t suffered or been scared, that he had gone quickly and peacefully. I wished I could hold him in my arms, caress his hair, and make everything okay.

Within 48 hours of hearing the news, I was sitting with my cousin and sister on floral bedsheets on my cousin’s cast iron bed when I got a call from the funeral home. The man on the line said that due to Covid,

I would have to identify my brother’s body via a photo he would send to me. His message popped up within minutes.

I immediately felt nauseated. “It’s here,” I said. My sister, cousin, and I held hands and said a prayer before opening the attachment. And there it was: a photo of my beautiful brother, lifeless.

My sister howled. “No, no, no, it’s real now, it’s real now,” she kept repeating.

I held her tight. We wanted to ask that photo, ask our beloved brother, “How did this happen to you, baby?” I began to caress his face on the computer screen with my index finger as tears poured down my cheeks. I just wanted to tell him, “I’m so sorry, Fahim, I’m so sorry, Fahim. My poor, sweet brother. My heart.”

My father heard our cries and knocked on the door, asking what was going on. We quickly shut the computer, wiped our faces, and told him we were fine. We could never tell him what we had seen.

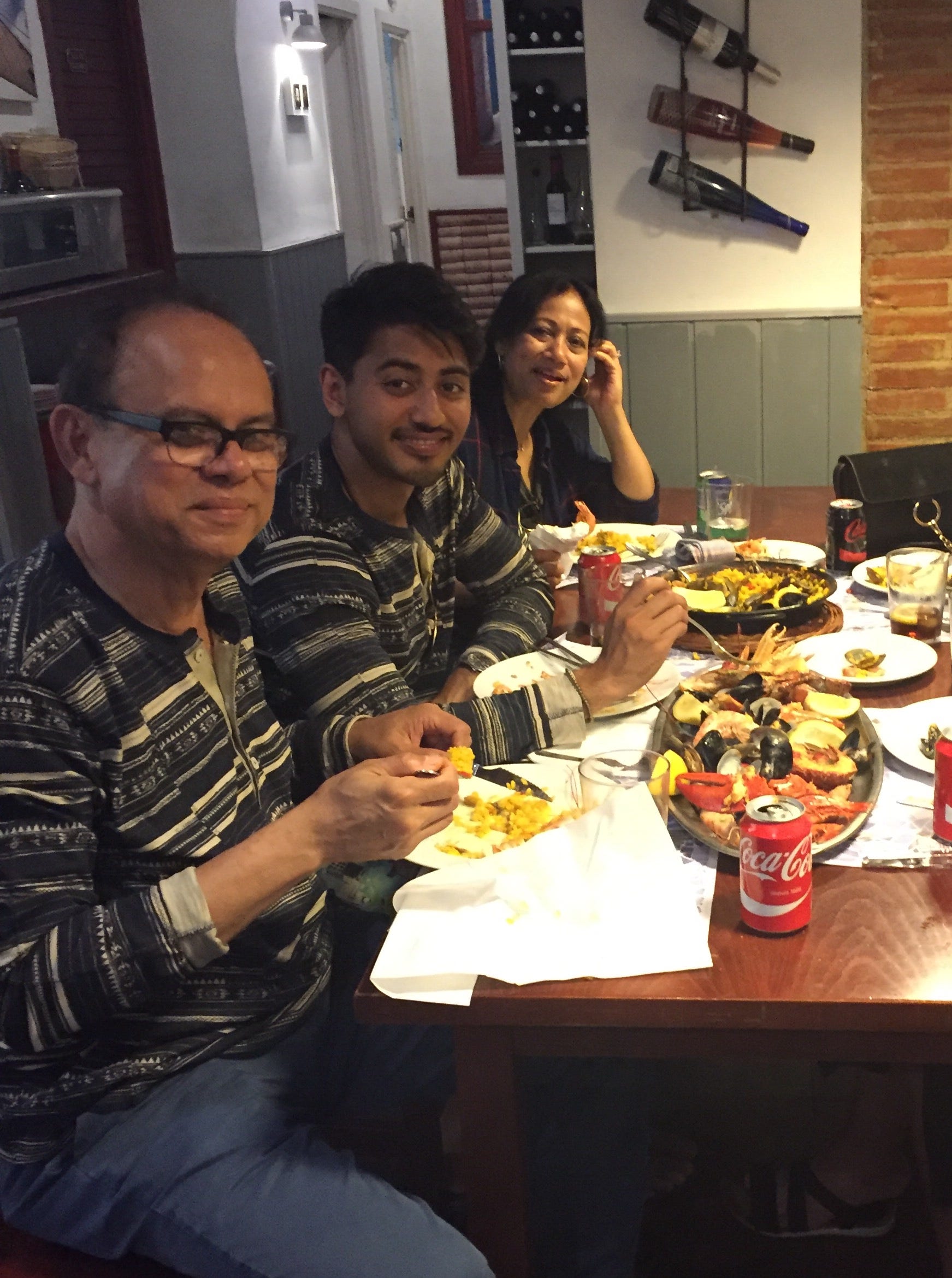

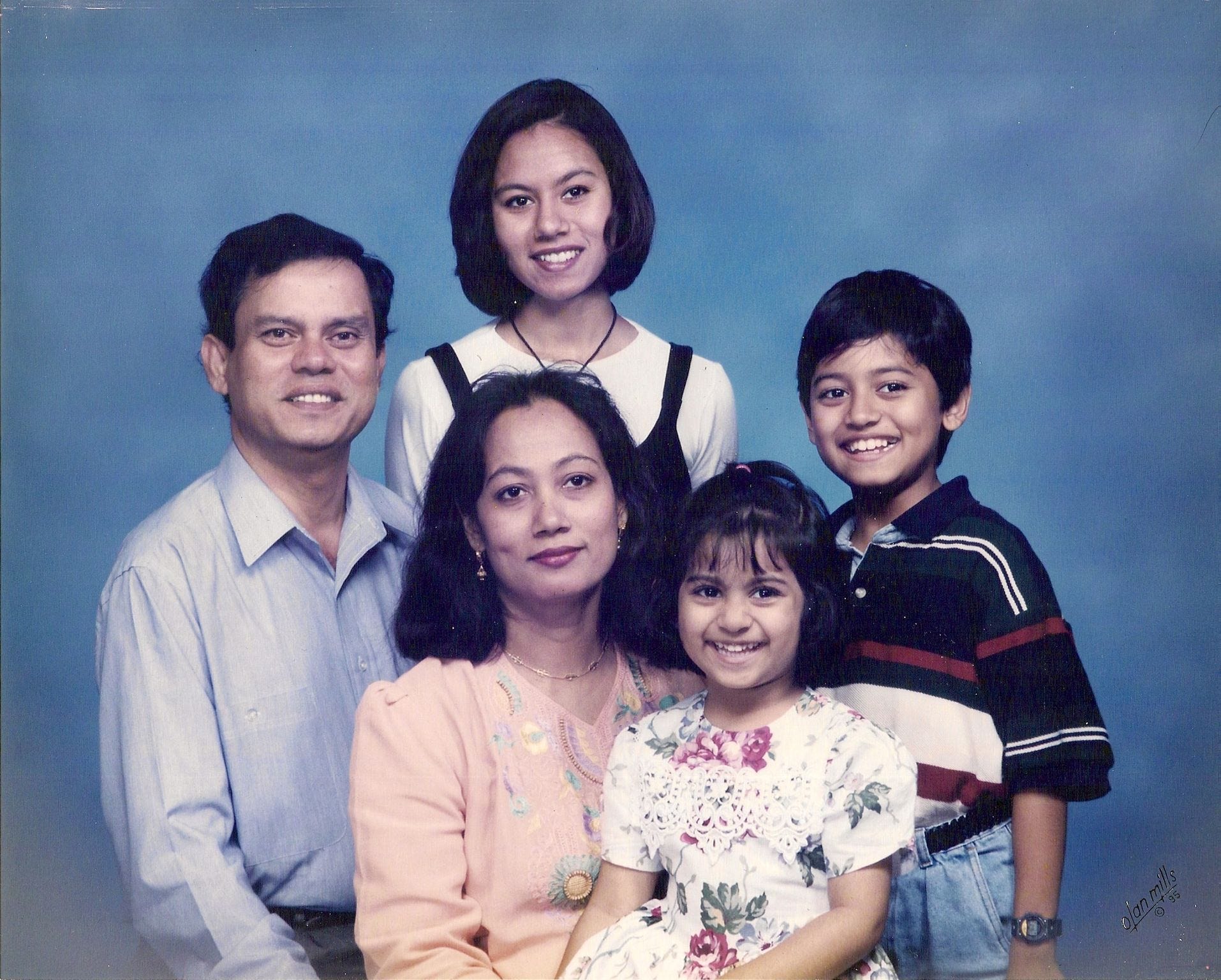

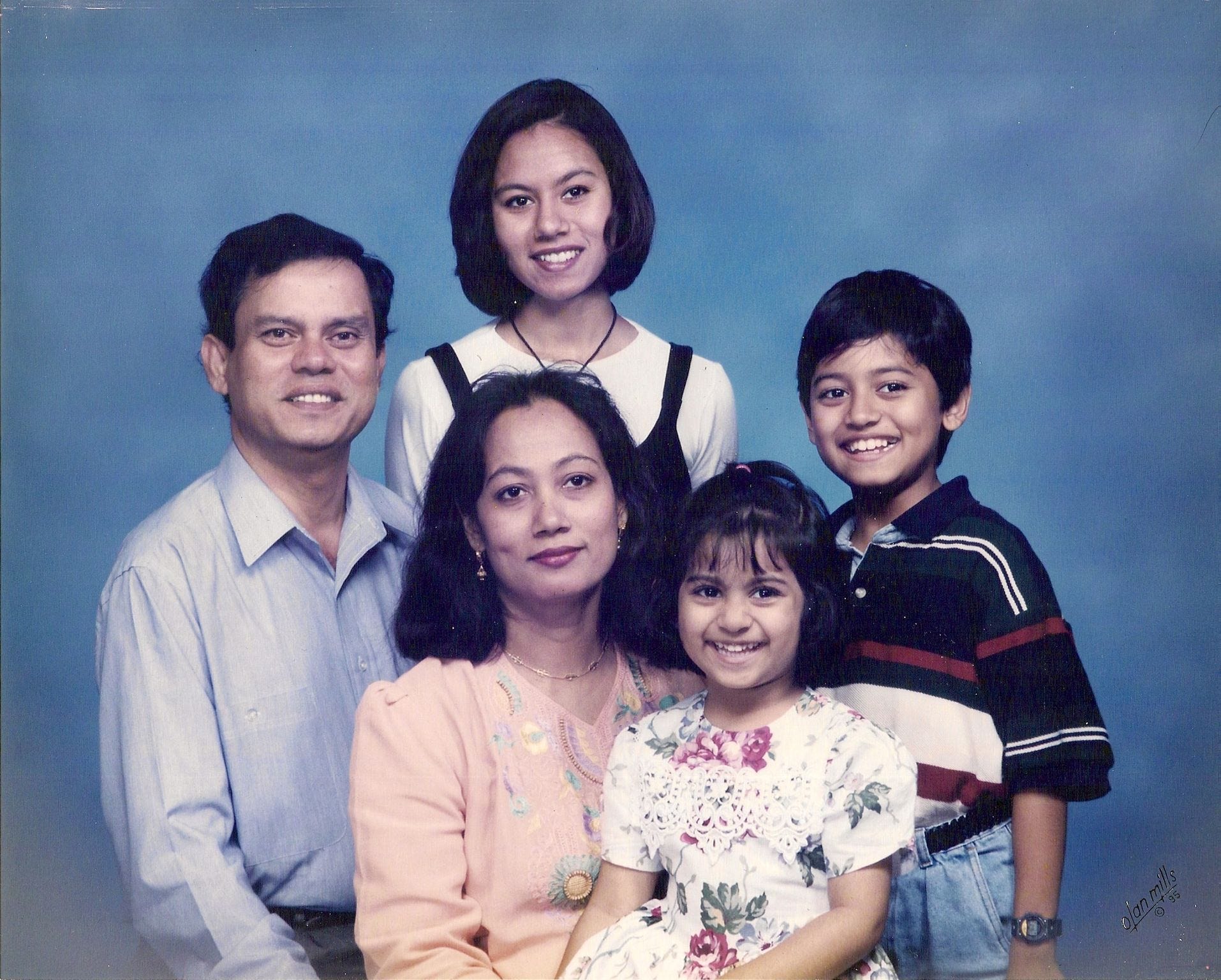

Our family is originally from Bangladesh. There, my father worked as a canvas salesman and we were considered lower middle class. In 1985, after receiving his degree in Computer Science, he accepted a professorship in Saudi Arabia and relocated our family of three to earn a better living than he could in Bangladesh.

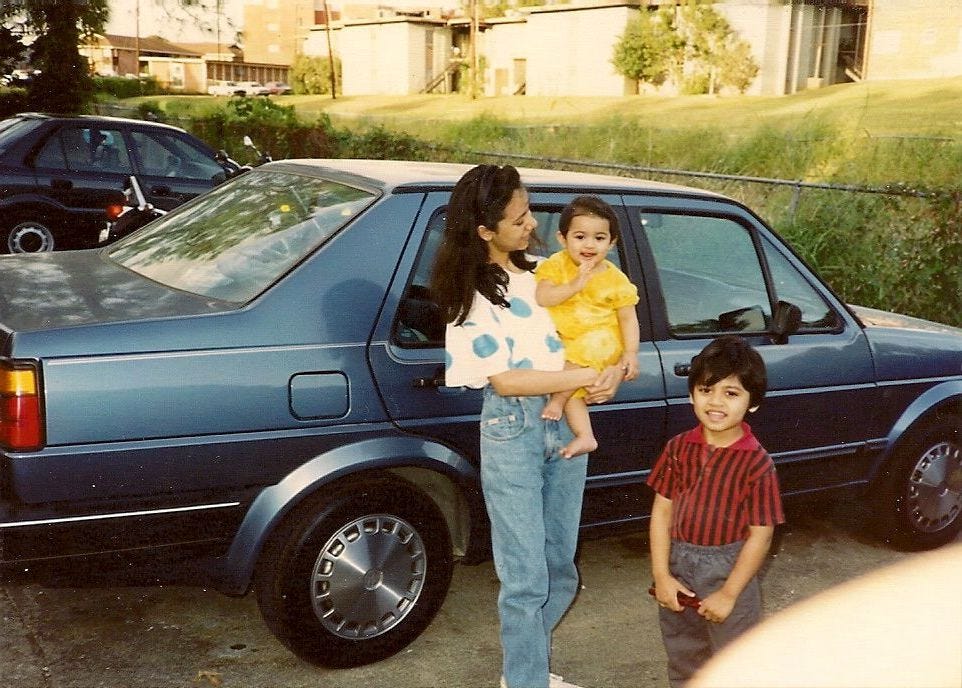

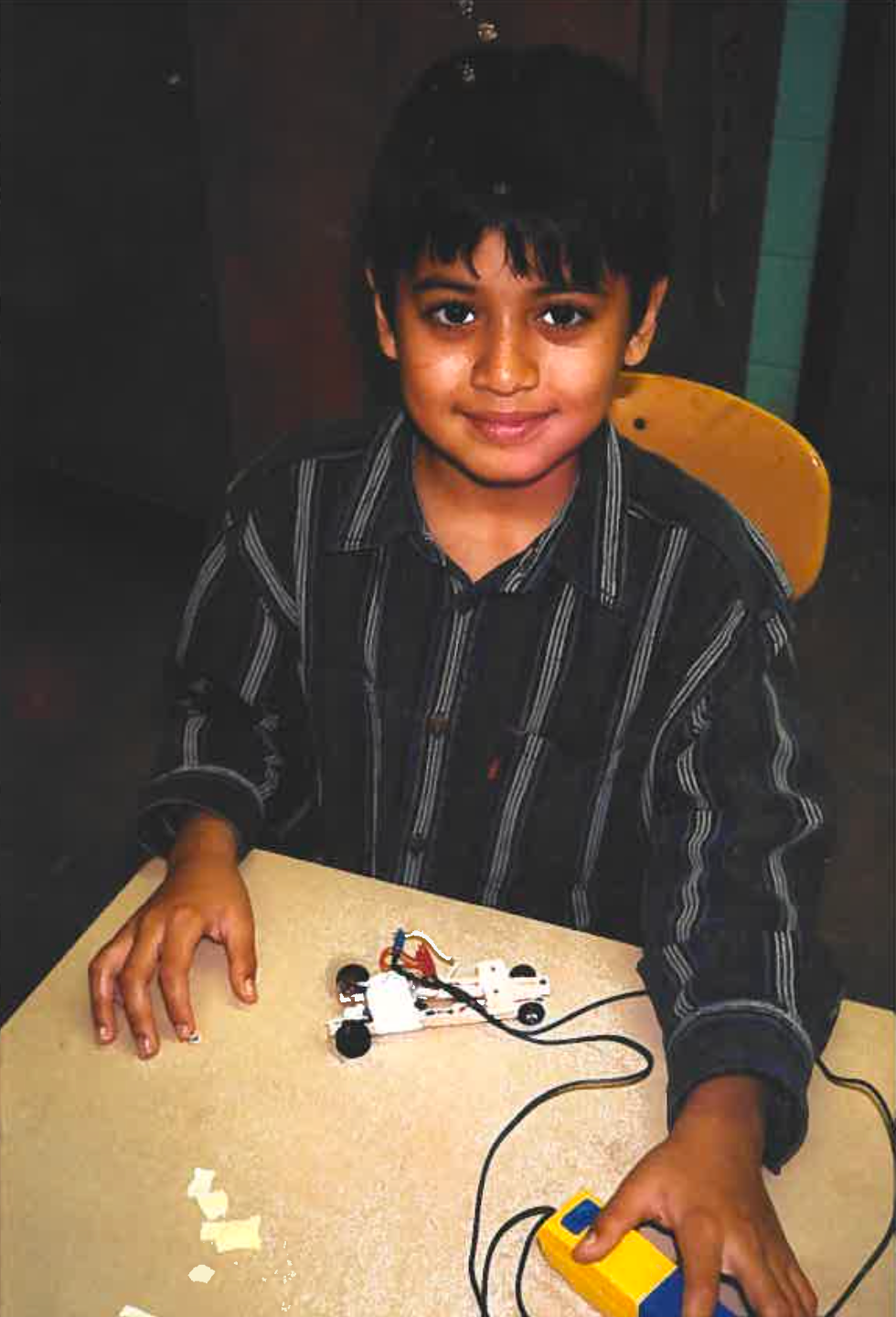

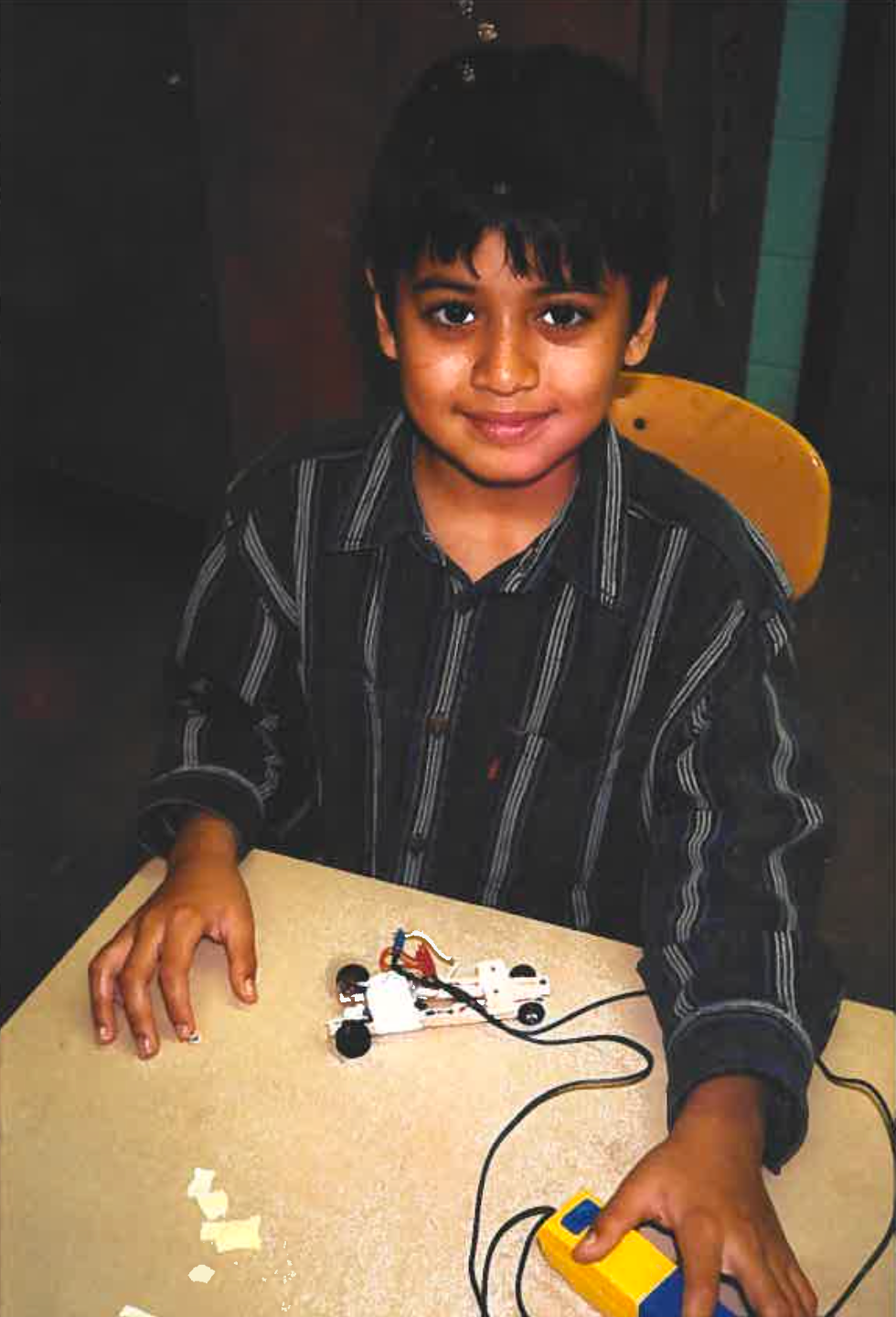

Fahim was born in 1986. He was a precocious, curious, active, and happy child. His love of technology began early. Any time he received a toy, he would take it apart to see how it was built. As I got older, our father began to worry about my education, so in 1991 when I was 12, Fahim was four, and my sister was a baby, we moved to the US.

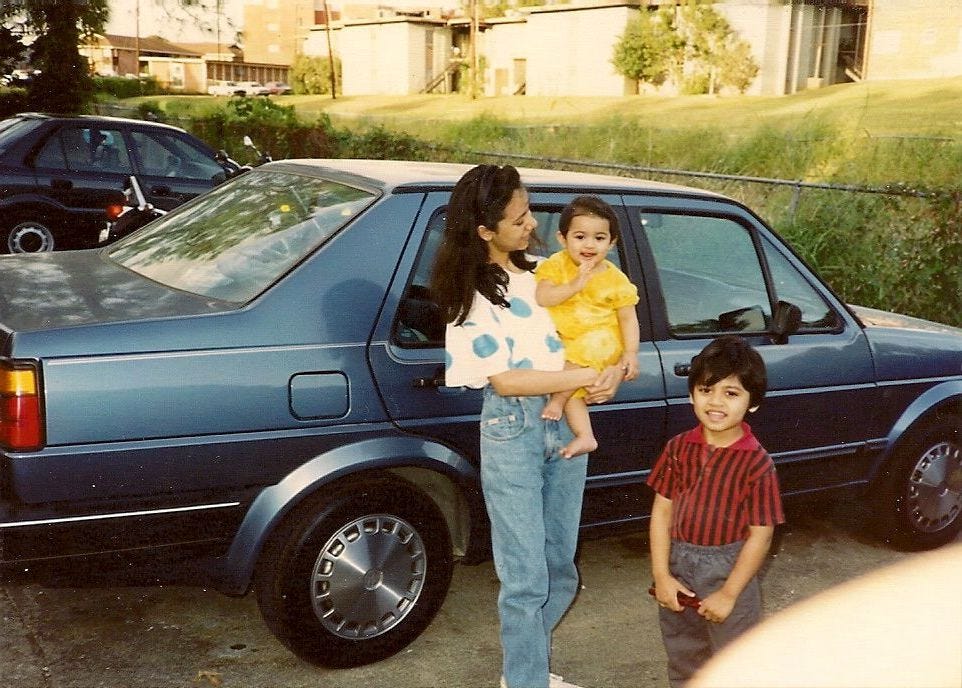

We settled in Louisiana, where our father pursued a PhD in Computer Science while our mother worked at a local laundromat.

Our family of five lived on my father’s small stipend, the minimum wage my mother earned folding other people’s clothes, and some loans from relatives. That first summer, I babysat for one dollar an hour. For a long time, I owned only five t-shirts and two pairs of pants.

The stress my father endured during those years in Louisiana was palpable in every corner of our tiny two-bedroom apartment. “No one moves to America this late,” my father would lament, referring to relocating a family of five instead of a newly married couple, as most of his peers had done. “You don’t get anything free in America. It will take us many many years to feel established here,” he would say, his elbows planted on the dining table. He would close his eyes and massage his temples with his thumbs, the rest of his fingers forming a tepee around his forehead.

It was difficult for Fahim and me to see our father in constant hardship. Wishing to ease his burden and pain drove both of us to succeed.

When Fahim was ten, he began buying candy from the local dollar store and selling it at a mark-up to his schoolmates during recess. Once word got out about his venture, the school principal shut it down.

A few days later, Fahim asked our dad for a jewelry-making kit, an advance on his birthday present. Then he made and sold beaded bracelets and necklaces in the neighborhood playground. That was his second business.

Fahim’s passion was technology and his brilliance was his endless creativity and curiosity. When he discovered the Internet, he finally had a way to channel his God-given gifts. He was 12 when he built his first website, “The Saleh Family”. I wish I could remember the exact description he wrote next to my photo, but it was something to the effect of, “This is my big sis. She’s cool but I don’t like when she steals the remote from me.”

Fahim quickly discovered that he could make money on the Internet by creating websites.

He monetized his first website in 1999, when he was 13 years old. By then, my parents had moved from Louisiana to Rochester, New York, and I was in college less than two hours away. The site was called Monkeydoo: jokes, pranks, fake poop, fart spray and more for teenagers.

Our father worried when the first $500 check arrived in the mail from Google, addressed to Fahim Saleh. How is this boy making $500? That is so much money, he would later tell me he had thought.

Our father’s relationship with my brother was very special. They were so different: Our father worried too much, while Fahim never worried.

Fahim was the only one who could placate him. He showed our father the website and explained the programming languages he had used to build it.

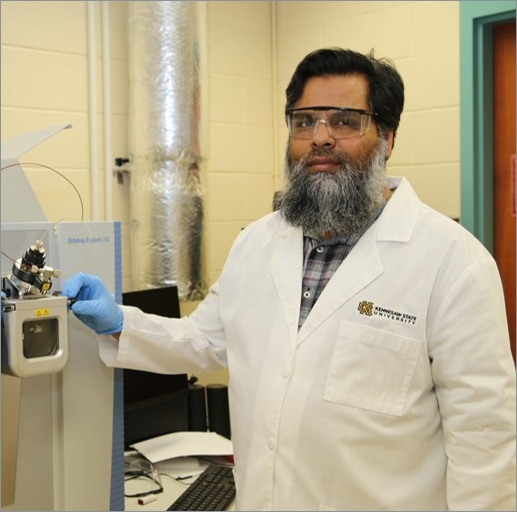

Because our father was a programmer himself, books about computer programming filled the shelves of our house.

Fahim had used those books to teach himself. “Teenagers are visiting the site, Dad,” he said, “and I’m monetizing their visits with ads from Google.” Though he understood programming languages, our father knew nothing of the Internet. But Fahim convinced him that there was nothing to worry about.

Then he asked for permission to open a bank account in his own name, because he knew he would continue to receive paychecks. Our dad worried about giving a 13-year-old his own bank account. But as always, Fahim convinced him that everything would be ok.

From the time he discovered the Internet until the time I last saw him, my brother could get so lost in his work that the sun could come up before he realized he had skipped both lunch and dinner.

Our father fretted over Fahim’s habits. When Fahim was a child living at home, and later, whenever he was staying with our parents, our father made sure Fahim was fed while he worked.

He would bring him what my sister and I coined a “surprise sandwich”, the most random concoction of whatever was in our refrigerator that day. When our father dropped off food, Fahim would discuss his latest project with him, his big beautiful eyes, with those long eyelashes

I was always so jealous of, alive and bright. Whenever Fahim wasn’t home, our father worried that he wasn’t getting enough to eat.

“How will I survive knowing that I never again have to worry about what my Famy ate today?” he asked me the day after the funeral.

When our father was forced to retire from his job as a computer programmer a few years ago, Fahim sent our parents a monthly check to ensure that they were taken care of.

Even before that, he had been wiring our mother a monthly allowance to fund the things that made her happy: decorating and redecorating our living room, buying costume jewelry and the nice shampoo she likes.

Whenever we went out to dinner as a family, we never let our father pay. While Fahim was in college and I was working, I always picked up the tab. But from the time he got his post-college venture off the ground in 2009, Fahim treated us.

Our father would reminisce during those dinner outings about our struggles in Louisiana, those years when the only restaurant experience we could afford was the $3.99 Saturday Meal deal at Domino’s.

Every Saturday, sitting in our father’s blue second-hand Volkswagen, we would share the large pizza and bottle of soda. It was the highlight of our week. “Nostalgia,” our father always says when we talk about it.

In 2003, when he was seventeen, Fahim met K on the internet, a boy from Ohio who would go on to become his longest running business partner and best friend.

Together they started a venture called Wizteen, designing Avatars, or Dollz, as they were known as then, for AOL AIM and other messenger services. Through their earnings, Fahim became financially independent by the time he was a freshman in high school and saved enough to put himself through college at Bentley University. He had accomplished his goal of easing our father’s burden.

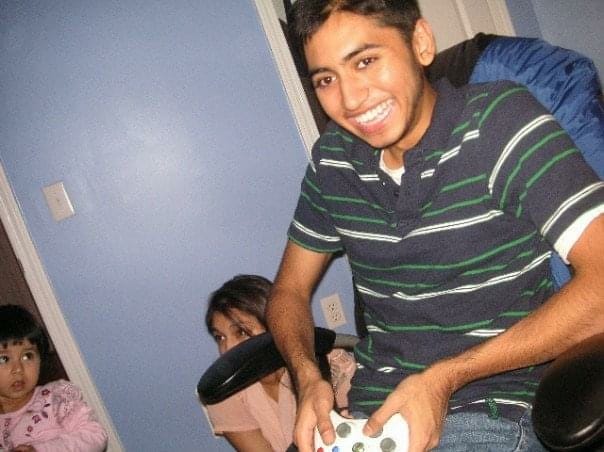

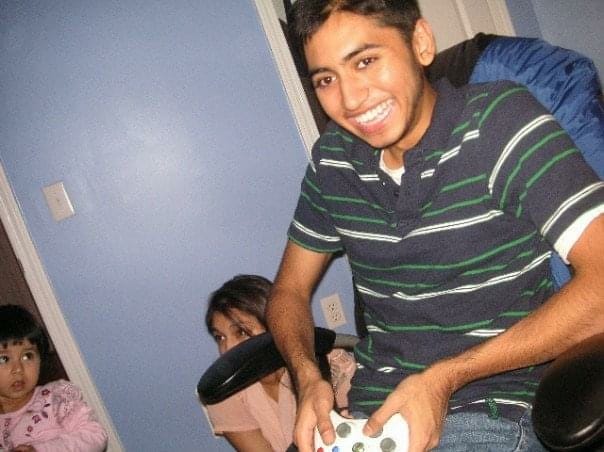

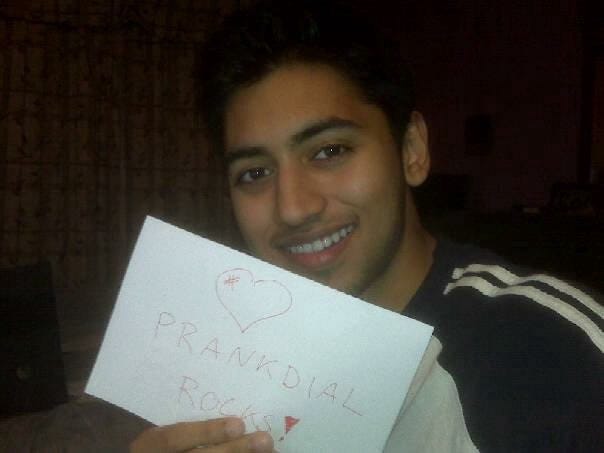

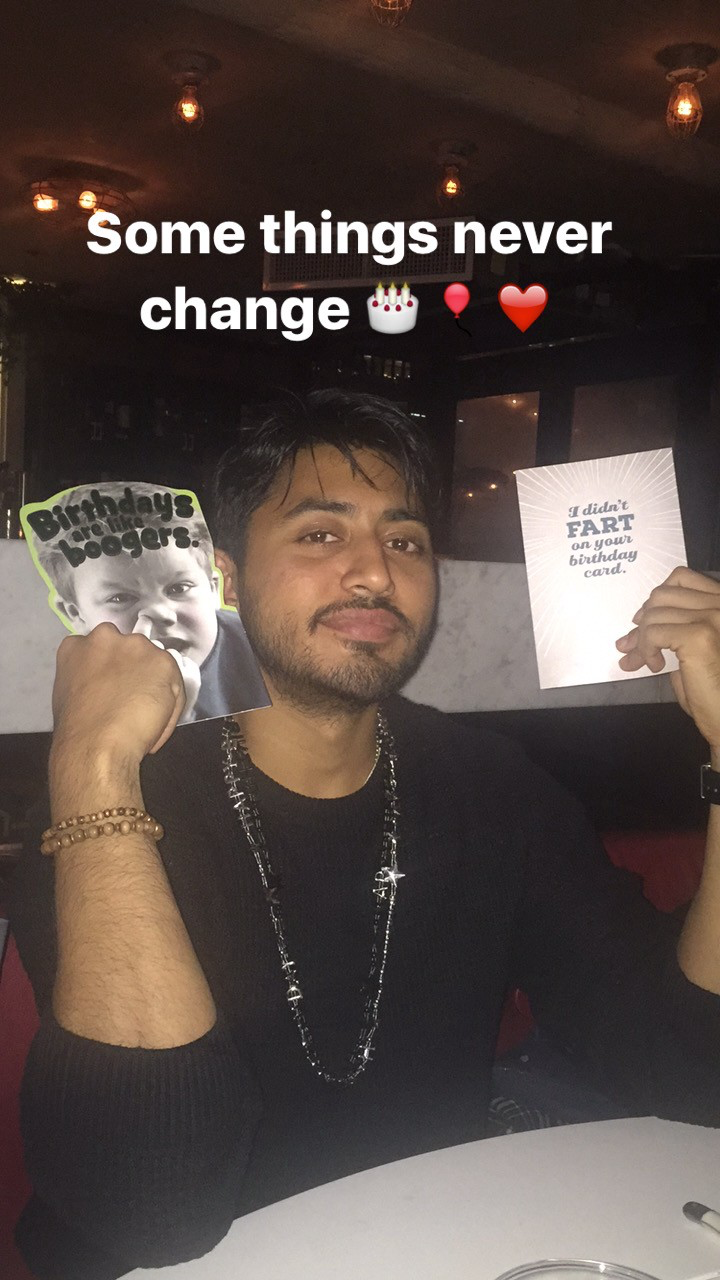

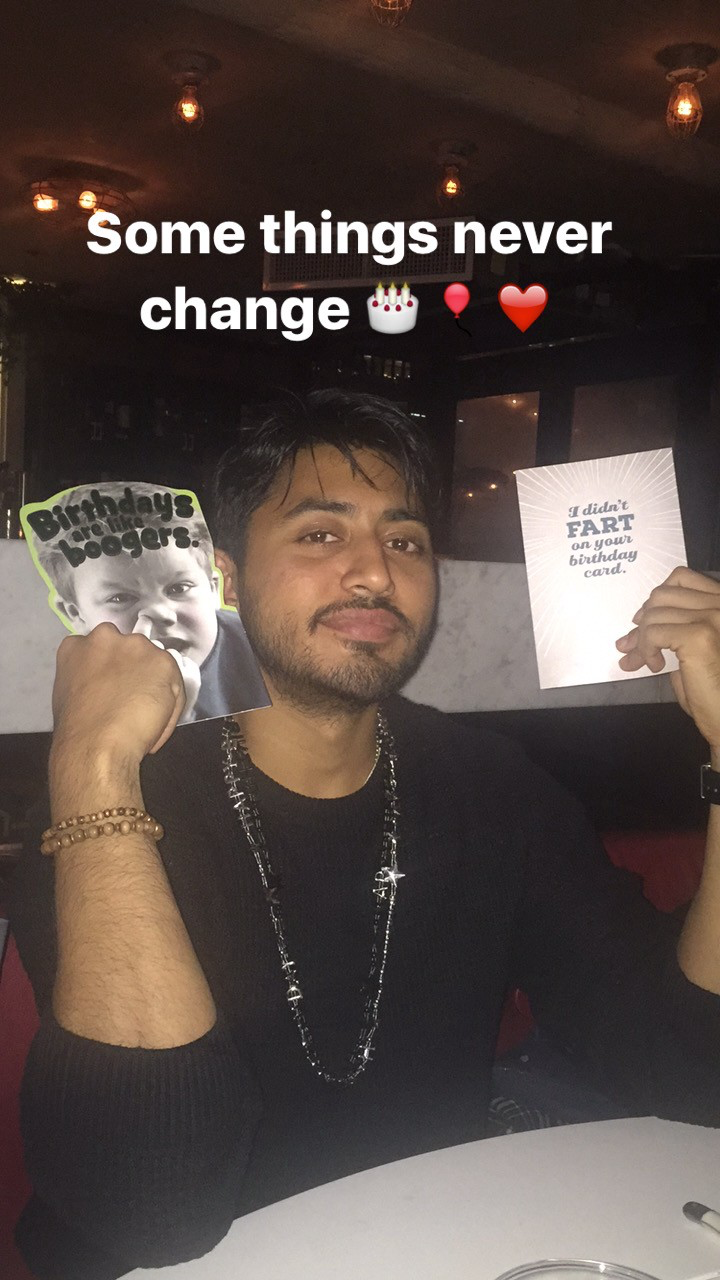

When Fahim graduated in 2009, the job market was in distress and Wizteen was no longer generating much revenue. He turned down a $50,000-a-year IT job, opting instead to spend months in my parents’ basement building his next product. PrankDial was born of one of my brother’s biggest hobbies. Pranks and surprises were such a big part of Fahim’s personality that whether he was home or not, we always knew one or the other was around the corner.

In 2018, while working in Nigeria, he flew over 5,000 miles to surprise our mother in New York with flowers on Mother’s Day.

Another time, he posted an Instagram story of our mother: He sneaks up on her while her face is smeared with turmeric for a beauty routine.

A few seconds later, she notices him filming, squeals, and runs away, as Fahim breaks into his infamous cackle. On yet another occasion, Fahim held a family dinner at his place and purposely left his poop floating in the toilet for my cousin, A, who was waiting to use the bathroom.

The last time I saw Fahim was a year ago: he flew to another continent to surprise me and meet his new baby niece.

Fahim’s brain was a bottomless magic hat of ideas big and small, wacky and serious, local and global. You never knew what he was going to pull out next, but he got to work on every idea immediately.

He couldn’t let one sit; he was too excited to usher the vision in his head into the world for the rest of us to enjoy.

At 33, his business interests had matured from expressing his love of jokes and pranks to changing people’s lives through technology in the developing world, while employing the most impoverished of them.

Having come from so little, Fahim had zero interest in being a rich entrepreneur who only hung out with other rich entrepreneurs. His heart was most open to those in need.

“These drivers depend on me,” he would say when talking about Gokada, the motorbike-hailing app he developed in Nigeria. Just as he had once been determined to ease our father’s hardships, he later dedicated himself to easing the hardships of countless others.

In recent years, he was maturing not just professionally, but personally. He was so excited about decorating his new apartment and would discuss throw pillows with our mother over Facetime.

He was developing his passion for cooking, working on improving his running performance, and taking care of his three-year-old pomsky, Laila.

He was creating structure and stillness in his life, neither of which came easily to him . He was making so many plans for his future.

But on Sunday, July 19th, 2020, my family and I had to bury my sweet brother in the Hudson Valley. I had to arrange my beautiful boy’s funeral. Three days prior, the funeral home called to report that it would not be possible to sew his limbs and head back onto his torso before burial. Upon receiving that news, I closed my eyes and crossed my arms over my chest like a Pharaoh, squeezing my phone against my body. My hands formed fists that I pushed into my heart with all my strength to contain my pain. Then I pleaded with the man to make sure all of my sweet brother’s body parts were in their proper places in the casket. The day before the funeral, the man called me again. “It wasn’t easy, but we were able to put him back together,” he said.

The morning of the funeral, I laid restless and limp in my sister’s bed at 3 a.m. listening to my parents sob together in Fahim’s room, with the checkered bed sheets and our childhood photos on the wall, their conversation too muffled behind the wall to understand.

The day turned very hot. A panoramic view of the grounds would have revealed us on green grass, surrounded by statuesque trees whose leaves swayed in the breeze. My family and I looked at our sweet boy’s face in the casket. He seemed to be sleeping peacefully. His body was covered in a white sheet, ice packs placed on his torso, his beautiful eyelashes long and lustrous against his skin. His hair was matted down, not spiked like usual, its blond tips glistening under the hot sun.

Our fatherfather approached the casket and began to speak to Fahim in the affectionate voice with which he often addressed him. “Fahim Saleh, didn’t I tell you not to dye your hair? Didn’t I tell you?” he said before he began to sob. Our mother kept repeating, “Ok, you sleep now, baby boy. You get some rest. You sleep now.”

As the cemetery workers lowered my brother’s casket into the ground, my father stood at the head of the grave and shouted, “Fahim, don’t go. Fahim, don’t go. Fahim, Fahim, Fahim, Fahim….”

On July, 13th 2020, exactly one month ago, my brother returned from a three-mile run and was murdered in his apartment.

Sometimes it still doesn’t feel real that Fahim is gone. And sometimes it feels too precisely like the cruel, heinous, and unbearable reality that it is, letting me see nothing but darkness and feel nothing but piercing pain in every quadrant of my heart.

As I reminisce about Fahim, I know that he was the most special gift given to us, and then taken away.

Now, our father spends his days sitting next to Fahim’s dog, Laila, speaking to her in the same affectionate tone he reserved for my brother, watching videos of or reading about the accomplishments of his deceased son. My mother spends her days crying. At night, she cannot sleep.

Thanksgiving, our family’s favorite holiday, will be especially difficult this year. Fahim always made the garlic mashed potatoes, while I made the stuffing and my sister made her famous mac and cheese.

Maybe I’ll host Thanksgiving this year, I thought to myself last week, instead of having it at my parents’ like we usually do. Where I live, it’s warm year-round.

Maybe in this new setting, we will all feel a bit less heartbroken when Fahim doesn’t tear through our parents’ kitchen door, running behind schedule, letting in the cold air behind him, throwing his jacket and bag on the floor, taking his place at the kitchen island, surrounded by his family, Googling garlic mashed potato recipes on his phone.

Releted: ফাহিম সালেহের খুনী যেভাবে ধরা পড়লো